I have been reading through the memoirs of my late mother, then Elizabeth Willett, and trying to “decode” them. Because she was adopted she changed names and places to protect the anonymity of her birth family. However she encoded almost everything – even events that had no bearing on her birth family!

Most recently I have been looking at her description of being evacuated at the beginning of World War 2. Her details in the 1939 register are still redacted (it takes some time for them to unredact details of recently deceased people – it seems they are running at least 15 months behind), so I was not sure where she was sent.

She recalls the preparations for war without realising the impact.

All this [War Preparation] really passed me by. I was not yet nine years old and couldn’t imagine my life changing in any way. It was decided not to keep me in Wimbledon but to send me, together with Marie Anne my adored Swiss governess, to join my day school which was evacuating to a country mansion, well away from the expected bombing.

Mummy took us down there and my heart sank as we drove up the dark lime avenue to an awesome Jacobean house.

Faulder, EP., Unpublished Memoirs

As a child her adoptive parents, Everard and Elizabeth Willett, lived in Wimbledon. A query to Wimbledon High School confirmed that my mother was a pupil there from 1937 to 1939. They also allowed me to browse their archives and searching on “evacuation”, brought forward information about Wimbledon High School partially evacuating to Hanford House near Blandford in Dorset.

Photo by Chris Downer – CC BY-SA 2.0

… In anticipation of hostilities Miss Lewis prepared in the summer a voluntary evacuation scheme for the younger children. Hanford House, near Blandford, Dorset, was taken and the children began to assemble there even before the Government evacuation of school children began. Miss Taylor, Miss Fryer, Miss Finnis, and Miss Wilson were soon on the spot, working hard to prepare the house for its new tenants and to black it out. Miss Lewis herself spent many strenuous days there directing operations. Soon work was in full swing. Miss Kerslake goes down for two days a week, to give lessons, take the children for walks and help to do all the multitudinous things that the very young need. The children dispersed for the Christmas holidays and returned again in a great bus for the Spring Term.

The Wimbledon High School Magazine (Issue 48) Page 7

In some ways this situation should have been idyllic – but the times were far from idyllic:

Together with the teachers, one or two other governesses, and one Norland Nurse, the school did its best to make us happy. Marie Anne was very brave to come with me rather than returning immediately to Switzerland, but the whole effort was a dismal failure. The staff were suddenly with their pupils twenty-four hours a day, cut off from the outside world down a depressingly long drive in a very rural area. They must have been profoundly unhappy.

Faulder, EP., Unpublished Memoirs

For a nine year old child, it must have been confusing – away from home with massive world events swirling around and great uncertainty as to what was happening in Europe. For my mother, it got worse:

On the first Saturday, in an effort to occupy us, a group were rounded up to clean the brasses in the family chapel. I remember skipping along fairly happily, quite looking forward to this new experience. Once inside we were given our individual tasks. I was told to go and get the cross off the altar and bring it into the vestry to clean. In horror, I firmly refused. I was too young to explain that I’d been taught it was sacred ground beyond the altar rail, and only priests were allowed there. The teacher insisted and eventually I was forced to go.

“Please God, I’m sorry”, I prayed, seized the cross and scuttled off to the vestry. Never has a cross been so well polished as I desperately tried to atone for what I saw as a mortal sin. I was actually praised for my efforts and then, oh horrors, told to go and put it back. Again, I offered a prayer, an apology and said I’d tried very hard to clean the cross before I backed away once more.

Faulder, EP., Unpublished Memoirs

My grandmother was profoundly Anglican in a sort of Edwardian style – with all its contradictions – and would have brought my mother up to be fearful of breaking the rules. This episode was profoundly unsettling to my mother and without the reassurance of home (despite some of its problems) she was vulnerable to further unsettling.

(altar rails long gone – space now used by the school choir!)

Photo © (Attribution & Notification) Peter Walker

Probably that memory would have faded like so many others but next day, Sunday September 3rd, worse was to come. We all trooped across to the chapel for service and filed into the pews. I remember peeping through my fingers at the twinkling cross as yet again, I begged for forgiveness. Then the rector told us we were at war with Germany. I was appalled. God had wreaked his vengeance, and I firmly believed the war was all my fault. I couldn’t tell anyone about my awful sin, imagining they would kill me for doing such a dreadful thing. Everyone was in tears and very upset, including the staff, so they were hardly likely to notice just another child sitting alone, white faced and shaking.

Faulder, EP., Unpublished Memoirs

In the afternoon, accompanied by my favourite teacher, our class climbed the steep hill behind the house and I decided that I simply had to tell someone. On reaching the top, our teacher stood somewhat apart as the group of children chased each other, and rolled down the steep slopes whooping with excitement. Very quietly, I approached her. Turning, she held out her hand and tried to smile, but tears were rolling down her cheeks and she couldn’t speak. Silently we stood, hand in hand, gazing through our tears at the beautiful view stretched out below. She poor dear was probably thinking of a fiancé, a brother, or other young men whose lives were now at risk. I only sensed that she was terribly upset so I couldn’t possibly confess that it was all my fault.

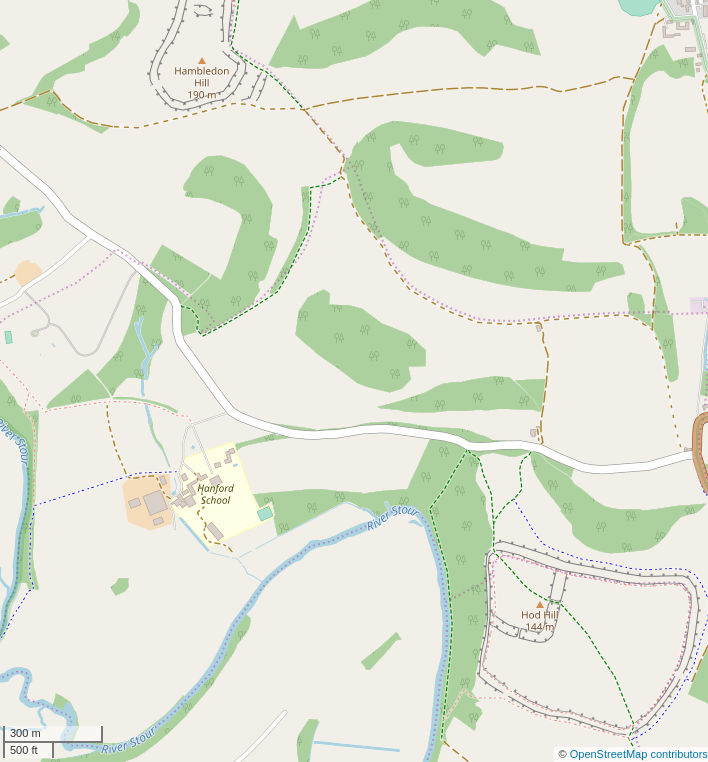

OpenStreetMap (CC BY-SA)

Locally the two hills near Hanford House are known as “Hod and Ham”; “behind the house”, probably means that the children climbed Hod Hill. My mother clearly felt she had nowhere to turn.

At about this time I started praying to my unknown mother. If she really was dead, I reasoned, she must be with God and perhaps she would tell him that I hadn’t meant to commit this awful sin. Then he would take the war away and we could all go home. I believed this theory quite passionately, and it served to ease my pain and shift a little of the responsibility.

Everybody was unhappy. We children slowly realised that we were not going to go home to our parents as we had all imagined. The governesses and nanny felt they were put upon by the teachers who wanted them to take responsibility for all out of school activities. The staff became tired and irritable, totally unmindful of the hard physical work the non-teachers were doing during the day, busy with the cooking, cleaning and all the other housekeeping chores.

I hardly saw my beloved Marie Anne who was worked off her feet and very worried about the prospects of getting home. Eventually she came and told me she had to leave. Her father was anxious that she should travel home across Europe to Switzerland whilst the lines of communication were still open. I felt very deserted as I waved good-bye to the pale tear stained face in the back of the taxi, becoming smaller and smaller as it disappeared up that awful avenue.

By the end of November, I was very poorly and, as there hadn’t been any bombing, Mummy decided she would take me home. I was violently sick in the car. Then, at last, I told someone about this awful sin. I longed to accept Mummy’s explanation, but was she being truthful this time, or just kind? Sensibly, she asked our vicar to call, and eventually all the strains and unhappiness were left behind.

Faulder, EP., Unpublished Memoirs

My mother did not return to Hanford, but spent the remainder of that academic year (1939/40) at an unidentified day school near Barton-on-Sea living with her mother at their holiday home nearby. This was assumed to be safer than Wimbledon – which did get bombed – but so did New Milton just inland from Barton-on-Sea in August 1940 (and again later in the war). In the autumn of 1940, not yet 10, she went to Sherborne School for Girls.

For others, possibly more robust, there was probably a degree of happiness.

The Junior School and Preparatory were evacuated to Hanford House near Blandford in Dorset between September 1939 and July 1940. This was a voluntary evacuation as Wimbledon was in a ‘neutral’ area. Some parents were so upset at the ending of the successful arrangement that their children remained there permanently, in the care of the owner, but no longer with the benefit of Wimbledon teaching staff

The History of Wimbledon High School (2005) Page 6

Player’s cigarettes. Coronation series, ceremonial dress; Public Domain

The “owner” in this case was Lieut.-Col. Frederick Hamilton Lister DSO. The 1939 Register records him as “member of His Majesty’s Body Guard”. This presumably means he was a member of the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen at Arms.

The 1939 Register for Hanford House (RG101/6960I/017/30 onwards) shows Lt Col Lister and (presumably – the register does not list relationships) his wife, Mildred, whose occupation is recorded as “Unpaid Domestic Duties & In Charge Residential Sub Of School”. I am assuming that the rest of the people at Hanford House were Wimbledon High School (WHS) staff (and possibly relatives) and pupils. The register also lists:

- two governesses (Misses Johanna Hurst and Marie Anne Wurstemberger),

- four assistant mistresses, (Mrs Edith Boucher, and Misses Phyllis Taylor (later Brown), Katherine Fryer and Elsie Taylor),

- a Matron (Mrs Mary Scott),

- one possibly two Children’s Nurses (Miss Alma Hobbs and one redacted record), and

- probably forty nine or fifty children (most of whose records are redacted – it may include children other than WHS pupils – there is at least one “under school age” boy in the list – possibly the son of the matron).

I think Marie Anne Wurstemberger would have been my mother’s Swiss Governess (different times!). Later in their lives my mother and grandmother were discussing all the governesses that my mother had experienced. My grandmother did not think it was remarkable that the governesses outnumbered the cooks – apparently it was difficult to find governesses who “got on with cook”. (!)

In 1947 the House was leased by the Listers to Reverend Clifford Canning and his wife Enid. (She was the daughter of Cyril Norwood, Head at Marlborough College and author of the Norwood Report, which led to Rab Butler’s 1944 Education Act.) They founded Hanford School – a Preparatory School for girls. When the Cannings retired the School was taken on by their daughter Sarah Canning – who was in the year ahead of my mother at Sherborne School for Girls.

Obviously the school concept was proven during the first year of the war!